At last, we have reached part 3 of this series on Unit Economics of Lending and how tech can help you to perform better on each metric. In this part, we’ll be focusing on two juicy metrics, namely, Expected Loss (a metric that is composed of Probability of Default, Loss given default, and Exposure at default) and Margin. Losing money is a part of every lending operation - the key is to have enough of a Margin to cover that loss, other costs that you incur and the required rate of return of your business as a whole.

If you haven’t read part 1 (focusing marketing & sales costs as well as cost of underwriting) and part 2 (focusing on cost of servicing and cost of financing), I recommend you to do so to get the full picture. However, if you have read those parts, you can skip the first section and head straight to the good stuff.

Unit economics in Lending

If you haven’t heard it by now, it is about time. Unit economics is a set of key metrics measuring how your business is performing. The precise definition of Unit Economics differs for every industry and can even be defined in various ways within the very same industry. This article goes through a set of metrics that we have defined for the Online Lending industry - but it can be done in many other ways. If you have suggestions on how we can improve on our break down, shoot me an email or PM me on Linkedin.

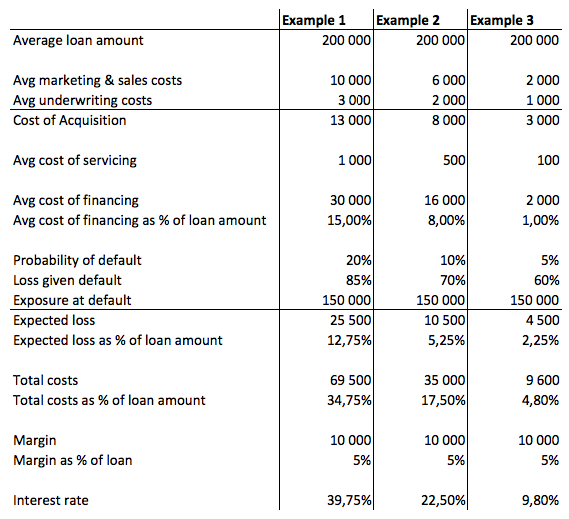

Below you find three examples of lending businesses and how they perform on various unit economics. For simplicity’s sake, we assume that each loan runs for 12 months. As you might have noticed, the numbers differ quite a bit between each example. This does not necessarily mean that one is performing better than the other. Being a high-cost or low-cost lender can both be the right strategy, depending on what market you operate in and what type of borrowers you target.

Marketing and sales costs describe how much you spend to acquire one customer that takes a loan. Underwriting cost is all about how much you spend on doing a credit assessment of a potential customer and deciding if you are to give it a loan or not. Cost of servicing describes how much you spend on collecting payments from your customers and cost of financing shows how much you pay for the capital that you lend to your clients. For all of these numbers, it is important that you look at your total costs and divide them by the number of loans that you have issued. For more details on these metrics, please read part 1 and part 2 of this series.

Alright, enough repetition, let’s get into the details of the Expected loss metric - a controversial one that makes the heart pound of any lender.

Expected loss

Having loans that default is a natural part of any lending based business and is unavoidable in the long run. The expected loss metric is an important one when looking at the unit economics of lending and can be broken down into 3 sub-parts; the probability of default, the loss given default, and the exposure at default. Multiplying these according to the following makes your expected loss

Probability of default * Loss given default * Exposure at default = Expected Loss

Let’s have a look at each one of these.

Probability of default

In simple terms, this can be described as the probability that a loan will not be paid back. A loan is considered defaulted if your client has not repaid you after a certain amount of time. The exact time depends on what your business is, but it is common that a loan is considered as defaulted after 90-120 days of your client not having paid its latest installment. If you run a regulated business or are reporting to shareholders, the exact number of days has to be defined to make it clear.

Obviously, it is impossible to say what the exact probability of default is before underwriting a loan. This is rather an estimate of what one thinks is the probability. Or, it is a probability that describes a historic view of your loan portfolio.

Having a high probability of default is not per se bad, as long as you are aware of it and have adjusted your business strategy accordingly (higher interest rates, optimizing loss given default with securities or a debt reselling deal, etc.). The key is to be accurate in the default prediction so that you can execute your strategy and have high confidence that things will turn out as planned. The less accurate you are in your default prediction, the more likely that you will make big and unexpected losses.

What are common default rates?

Having a probability of default of 4-20% is not uncommon in online lending. You will probably hear investors/friends/smartasses telling you that default rates should be sub 1% because that is what the target default rates are at banks or because this other cool startup has default rates in that area. These people tend miss the fact that 1) many banks has the majority of their loan assets in mortgages, which is considered amongst the lowest risk assets around (sure, you will find crazy sub-prime lenders, but let’s skip those for now), and 2) startups reporting sub 1% in defaults either has a portfolio made up of completely new issued loans (i.e. the payments are not due yet) or they refinance loans that are not performing and keep the rolling the snowball until the doomsday come/they are big enough to realize the loss. Looking at a couple of comparables, we can see that Klarna had made allowances for credit losses of about 4% in 2019, which is a proxy for expected losses, which in turn is the product of probability of default and loss given default. So it is safe to say that their probability of default is north of 5%. Another example is Swedish business loan lender Qred which had default rates at around 20% in 2020.

So next time someone come to you and say that default rates of online lending above 1% are high - call bullshit on that person or smile to yourself knowing that the person has no clue what it is talking about.

How can tech help you

In order to achieve a good accuracy of your default prediction, you need to build up a solid database to build models upon. In order to do so, it is important that you collect the required data points about your customers at the point of time when your credit assessment is done and how the loans perform over time. Here, tech can help you to collect the right data points through API connections to credit bureaus or by scraping data from bank accounts. The key is to figure out what data points are the most important ones and collect those. Tech can also help you to structure your data in the right way to be able to access it later on to recalibrate your credit decision model.

Some high level things to keep in mind are:

- Collect data about your loan applicants (e.g. financial data, demographic data, sales channel data, metadata about applicants, etc.). Some specific things to think about:

- Hard data is better than soft data (e.g. age is better than looks in this case as the former can’t really be disputed)

- Official sources are better than applicant data (e.g. financial statements from tax authorities tend to be more reliable than mid-year reports). But take whatever you can get your hands on.

- Cash is king. If you are in the business loan field, aim to look at bank statements rather than financial statements, as the former is more tricky to fake or manipulate.

- Make sure to save the data in a good structure that allows you to go back and perform a regular analysis of it

- Enrich your applicant data with loan performance data, i.e. how the loans have actually performed over time. Some things to keep in mind:

- Shorter loan durations allow for a quicker collection of performance data as your loans will reach their due date quicker.

- Be honest with yourself, a payment not made in 90-120 days should be considered a default in your analysis. Anything else is putting makeup on the pig (sorry for the Swedish saying).

- Segment your clients and run your analysis on a yearly/quarterly basis

If you are at an early stage, make things simple for yourself and base your lending on external sources of probability of default (i.e. credit reports) whilst you collect enough data to start running your own analysis.

Loss given default

Alright, so your client has not paid its latest installment at the due date and 120 days have passed, i.e. the loan is considered as a default. So what’s next? Here there are three different routes to take, either you try to collect the loan yourself, you ask someone else to collect it for you and pay them for doing so, or you sell it to someone else who takes care of the collection. How well each one of these perform determines your loss given default, i.e. how much money you manage to get back in the end.

Selling portfolios

Let’s start with the alternative of selling your loan to someone else that will collect it for you. Sounds like a pretty clean option right, realizing your losses and being done with it? Well, things are not always that easy. The players who buy defaulted loans are companies such as Lowell, Intrum, Hoist, Arrow etc. Pre-2022 the market was flooded by consumer loans being sold and many of the players had become fat cats and were not interested unless the portfolio was big enough and has attractive types of loans. With increased interest rates and inflation the market is a shitstorm - portfolios of fixed interest rates are valued lower, borrowers non-interest costs have increased, etc. Anyhow, in general, you will find it difficult to sell portfolios of less than 3 MEUR consisting of less than 300 loans. Also, unsecured consumer loans are preferred, as compared to business loans. If you are selling consumer loan portfolios you could get up to 60-70% of the remaining loan amount, if the age of the portfolio is not too old. If you are selling business loan portfolios 30-50% tend to be more common, if anything at all. Some key factors that will affect the price you get are:

- Type of loan (unsecured consumer loan/business loan/mortgage/etc)

- Collateral for the loan (if any)

- Size of the overall portfolio

- Concentration rate (sum of loans divided by number of loans)

- Age of the loans (i.e. how much overdue are the payments)

- Type of borrowers

Another option of selling loans when they hit default is getting a forward flow deal. In simple terms, this involves setting up an agreement with a company as the ones mentioned above, which will buy each loan as soon as it defaults to a predefined price. In order to get such a deal in place you need to open up your books and present the buyer with details on who your customers are and what underwriting processes and policies you have in place.

Using debt collectors

This also seems to be a pretty sweet option right? Not having to chase borrowers and taking the painful discussions on why they cannot pay and how they should try to do it. In many cases it can become pretty tragic when trying to collect a loan. After all, borrowers are people and if they cannot repay a loan they are in a pretty bad financial situation that one should be empathic about.

However, paying someone else to collect the loan for you comes at a cost. This cost tends to be on a success basis. I.e. if the debt collector is successful, it can take anything from 5% up to 50% of the owed amount. In other words, it can easily become a costly alternative with an uncertain level of success. In order to decrease your costs, try to set up an agreement with a debt collector so that it starts the collection process as soon as a loan has defaulted.

Handling the collection inhouse

Every lender should at least undertake some proactive measures to collect loans. This involves 1) making payments easy for the borrowers and 2) sending reminders. You can read more on this topic in part 2 of this series.

If you are doing the collection inhouse, it is all about trying to optimize how you get in contact with the borrowers (letters, email, phone, text message, whatsapp, etc.), how you communicate with them, and what options you present them with. What do I mean with options? Well, the reason a borrower doesn’t pay tends to have to do with two things, either it does not want to repay you or it does not have the money to do it (or a combination of the two things). If the borrower cannot repay you according to the agreed schedule, you can present it with options such as doing payments in smaller installments over a longer period of time for instance.

As mentioned above, handling collection inhouse easily becomes painful and is something that lenders should try to outsource if possible. Being best at lending doesn’t necessarily mean being best at handling debt collection.

How can tech help you with Loss given default?

To begin with, having your data in order is beneficial no matter how you handle defaults. You can use it to compile a comprehensive picture of your portfolio of non-performing loans (NPLs), provide debt collectors with useful information or use it yourself in your collection effort.

If you do choose to collect the debt yourself, having systems in place that will allow you to do this in an efficient manner is key. Sure, sending an email once to remind a borrower that it needs to pay does not require a lot of brains. However, once the number of non-performing loans and partial payments starts to pile up, keeping track of how debt repayments are to be split and what has been paid when easily become a mess.

Lastly, making things easy for the borrower is key. So have another read on what we mentioned in part 2 about payment methods, reminders and recalculations.

Exposure at default & Expected loss

Alright, so we have come to the final couple of numbers in the default saga. Exposure at default is simply the amount that a borrower owes you at the time when the loan is classified as a default. There is not much magic to this, so I won’t go through it any more in detail. There are some tactical approaches you can take in terms of what loan you offer your clients - like if you are offering an annuity loan or an installment loan, the duration of a loan, etc. - but I won’t go through them in any more detail here as they are not really interesting from a tech point of view. Hit me up if you want to have a chat about these.

Et voilà, multiplying your Probability of default, with Loss given default and your Exposure at default finally gives you your Expected loss. In this calculation, it is important that you look at your average numbers again.

Total costs, margin & interest rate

After having summarized your costs it is time to look at margin. This is essentially what is left for your business to pay for all other costs that we have not mentioned, e.g. salary costs, rent, etc. PLUS your shareholders expected return on their investment. Clearly, if you have been enjoying the bull market for the last 10 years, returning anything to shareholders hasn't really been that important. With increasing interest rates, this is all the more important.

After having added your margin, you are left with the interest rate that you offer your clients. One can easily be tempted to add a fat margin on top of the other costs to ensure that one has enough money to pay for everything and show a nice net profit. But clearly, this makes your loan more expensive and less competitive, which again can be a tactic if you are targeting a certain segment of the market. Keep in mind that the larger your portfolio gets, the more competitive you can be on your margin and still make a lot of money by the end of the day.

We have come to the very end of this series and if you are still reading this it means you are either crazy or have found it interesting. Either way, feel free to reach out to discuss different approaches. And if you would like any support in building your system or any sub-part of it, get in touch and we’ll make sure to make it happen.

Over and out,

Philip

.svg)